What will the Inflation Reduction Act Really mean for Ag and Climate?

Sarah Mock & Alison Grantham

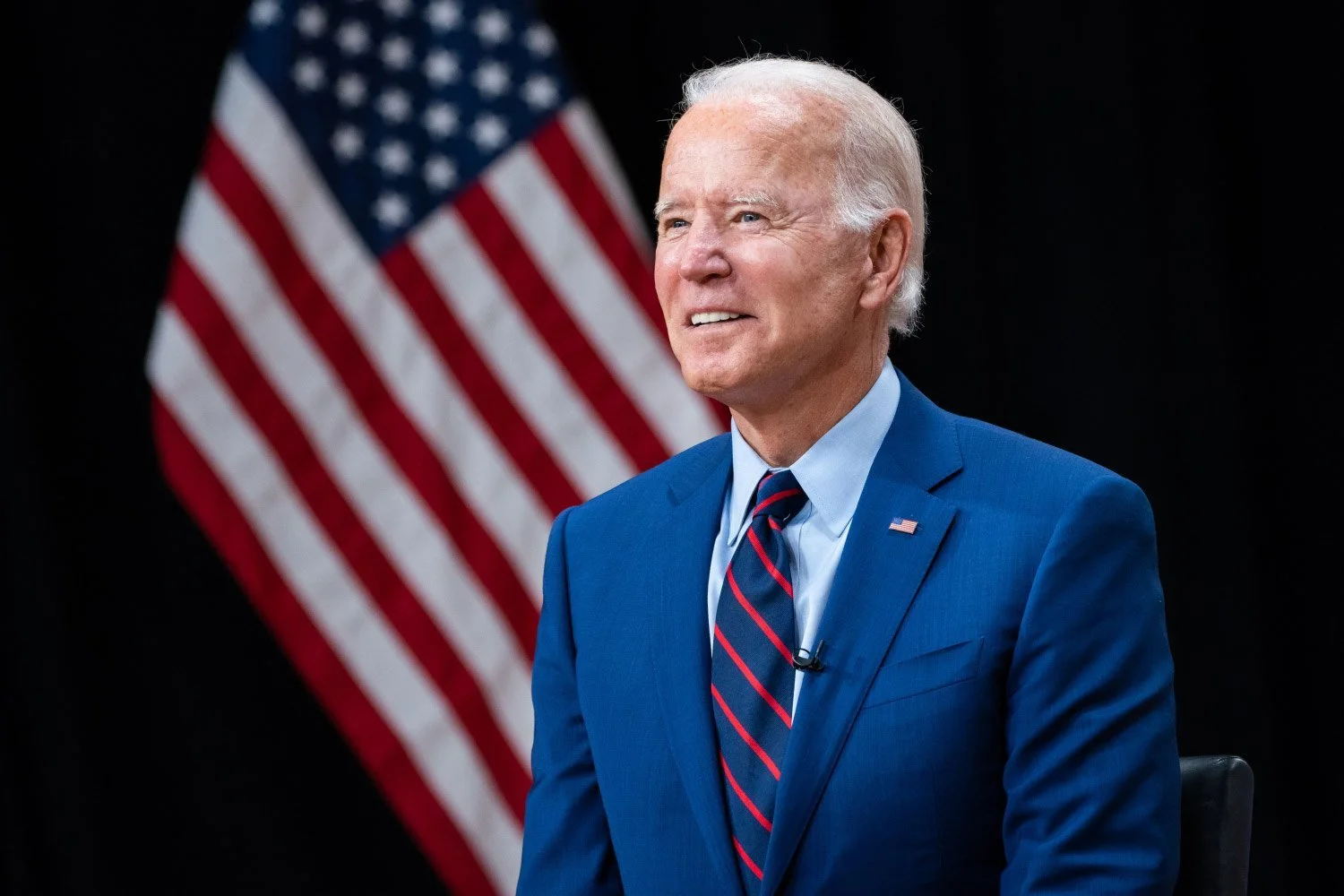

Today, President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, a Democrat-led +700B climate and tax bill.

The bill’s ag and food-focused initiatives have received some attention (though not nearly enough!) and we were excited to dig into the details and learn more about what all of these new funds might mean for transforming our farm and food system.

The overview of the ag portion of the bill is very much focused on climate change, notably, because an expanded investment in child nutrition funding was not agreed upon, and therefore stripped from the bill. That is a topic for another post, but I think it’s safe to say— healthy, well-educated people are a critical part of a resilient future. Investing in childhood nutrition is investing in climate.

Let’s get into the numbers:

Topline Agricultural Spending : ~$40B

~$20B for “Climate-smart Ag” Programs: Though the department has gotten deep into the lingo, most of these funds aren’t to go towards new programs, but rebranded existing programs, including CRP and EQIP. That’s okay! These programs have a good track record and good subscription rates. It makes sense to invest in them further. Further funding here will go to other financial incentives for farmers to adopt new practices, increase carbon storage, and limit greenhouse gas emissions.

~$14B for Rural development/communities: This includes loans for farmers and rural communities to invest in renewable energies, biofuel tax credits and infrastructure, including sustainable aviation fuels. From our perspective, this is a real mixed bag. Growing commodity grains to produce energy, from ethanol to biodiesel, is a dubious exercise in mitigating emissions— and especially when sustainable aviation fuel is in the mix (notably, this is not “plant-based” fuel, but a blended product, more like 10% ethanol gasoline). Investing in upgrading rural infrastructure is, however, a good investment not only in terms of reducing waste and improving quality of life, but also improving resiliency.

~$5B Forestry: These funds will go towards wildfire mitigation and carbon sequestration in forests.

~$4 billion for water resiliency in the West: These funds were the price of Arizona Senator Kirstin Sinema’s support, which will go to the Bureau of Reclamation to improve water infrastructure and store in the extremely drought stressed West.

~$3.1 billion for distressed borrowers of USDA loans: The $2.2 billion for farmers who have faced discrimination by the USDA is nice to see, but notably disappointing that it's the smallest figure out of all of these. So it's more like $50 billion, just to be clear.

What does this mean for American Agriculture?

The biggest takeaway here is that this, perhaps more than anything else, is a massive wealth transfer.

The top two lines here are definitely the most painful. We've thrown a ton of additional money at "climate smart" ag from USDA, despite the fact that the USDA is already giving out about a trillion dollars a decade to this same group of people just for owning farmland/planting crops. This group, of course, is farmers— specifically the 100,000 or so commercial scale farmers that USDA has had the longest relationship with. This group of farmers is, annually, on the receiving end of not only crop insurance subsidies (a la Title 11 of the Farm Bill), but also direct commodity payments (Title 1). These Title 1 payments are often in the hundreds of thousands of dollars annually range (see who receives payments near you, and how much, here).

The USDA is already dispersing these payments, using taxpayer dollars. It is possible to simply attach climate requirements to these existing payment— in other words, demand better outcomes in exchange for the US taxpayers continued investment— rather than gearing up the gravy train to give farmers even more to make marginal changes.

The back of the envelope math here is that, at best, 2.1 million US farmers are going to get some part of let's call it $30 billion, which split evenly would come out to about $15k. But we know with great confidence that there are not really 2.1 million farmers in the US, and that the vast majority of USDA funds go to about 100k of the biggest and most well-established farms. So the much more likely figure is that America's 100,000 biggest, most industrial commodity farms will each get in the ballpark of $300,000 from this bill. Mind you, that's not to switch production from corn and soybeans to fruit and vegetables to improve nutrition, or to pasture livestock to get them out of confinement. It's $300,000 to do things like plant cover crops (which every single state in the US already has a cost-share or grant program for, and which farmers can already sell carbon credits for doing), use conservation tillage (which nearly 3/4ths of US farmers already do), or do truly marginal activities like plant buffer strips around riparian areas or even install drainage, which we know for a fact leads to negative water quality outcomes downstream. So what will this $300,000 per farmer actually do for the climate? My guess-- at best, nothing. At worse, it's further capitalizing the most powerful in the industry, giving them funds that they can use to shape state and national laws to be even more lenient, for one.

All to say, it's disappointing, though not terribly surprising, that the bill turned out this way. Agricultural policy making in the US is very much shaped by state capture by the industry, both at the USDA and in Congress. These measures are only in a secondary way meant to improve climate outcomes. First and foremost, they're about what the USDA has always been about. Enriching (or their word-- "promoting") the existing power players US ag sector, and therefore maintaining and entrenching the status quo.

If not policy, what are the other options?

Voluntary corporate action, organized under the science-based targets initiative is one option that's gotten lots of attention and increasing traction, at least in terms of companies making commitments. Though, there are fair questions about whether those commitments are translating to impact or really just encouraging sneaky scoping (e.g., this report from February).

I was modeling some crop rotations and broiler house management scenarios in COMET this morning, and took a break to read this AgFunder piece from last week about PepsiCo's pep+ initiative. Pepsi did report 25% emissions reductions for the emissions under their control: both direct emissions (Scope 1) and emissions related to their electricity purchases (Scope 2), which sounds great. However, this scale of reduction is largely consistent with the greening of the grid in regions where PepsiCo operates (Our World in Data) over the period of their commitment (2015 -2021). So the degree to which PepsiCo deserves credit for this is maybe questionable, but still great that the emissions are moving in the right direction.

PepsiCo has also received quite a lot of attention and kudos for their scope 3 commitment (40% by 2030) and related regenerative ag initiative. Let’s dig into what they’ve accomplished.

So, did they make progress? Yes and no.

PepsiCo has calculated the primary production footprint (the land area where crops are grown that ultimately make their way in whole or in part into PepsiCo products) to be 7 million acres. There are many emissions associated with these acres currently. Lots of the emissions stem from use of nitrogen fertilizer, which is produced by burning fossil fuels to turn inert N2 gas which dominates our atmosphere into plant-available forms of nitrogen fertilizer. In addition to the emissions associated with its production, when farmers apply nitrogen fertilizer to their fields, microbes convert a portion of it to nitrous oxide, a potent and long-lived greenhouse gas responsible for roughly half of the ag sector's GHG footprint.

To tackle these emissions, at least in part, PepsiCo launched their regen ag initiative, dubbed pep+, to encourage farmers to adopt regenerative ag practices. They report some impressive progress on this front,

"345,000 acres of this farmland worldwide [4.9% of total footprint, my addition] are using regenerative agriculture practices. By the end of 2021, the company had 72 regenerative “demonstration farms” and over 600 farmers transitioned from demonstration stage into broader “landscape” impact programs around regenerative farming [it seems the scope of their program is 600 farms, b/c 345k/600=575 ac per farm, which seems reasonable]. In the US, PepsiCo has so far helped [what does this mean? cash incentive? cost share? technical advice?] farmers plant more than 85,000 acres [1.2% of PepsiCo acres] of cover crops."

Putting these numbers in relative scale makes them far less impressive when compared to overall trends. For example, in the US, cover crops were used on over 20 million acres in recent years (nearly 3x PepsiCo's entire farm footprint), or more than 6% of cropland in the US (compared to 1.2% of PepsiCo's supply shed; USDA-NASS 2022).

Also, what is a regenerative acre if it is not cover cropped? Just an acre with reduced tillage? That would make this even less impressive as reduced tillage is widely adopted on corn and soy acres in the US.

But even so, in the end even these modest adoptions of "regenerative" or "climate smart" practices on land in PepsiCo's supply shed did not support any reduction in Scope 3 emissions. In contrast, Scope 3 emissions INCREASED by 5%. And the explanation for this increase had nothing to do with farming.

Casual observers of this space might be forgiven for thinking scope 3 = farm emissions, as with food companies that has been the dominant narrative. However, there are lots of other emissions that fall into Scope 3, to include product manufacturing emissions when those products are made by contracted manufacturers (co-manufacturers/co-packers, etc.) rather than in facilities a company owns, leases, and operates itself. Emissions from these types of facilities are what PepsiCo attributed their increase in scope 3 emissions to.

The trend towards co-manufacturing in supply chain management is a form of outsourcing that has intensified over the last 2 decades as food producers look to reduce costs and decrease the time to market to produce new products. But, it also fundamentally shifts the structure of companies' emissions profiles, increasingly making most emissions scope 3, regardless of whether they're related to growing crops, processing ingredients, or manufacturing products.

This calls into question the value of the whole scope framing for corporate accounting. Would it be better to focus instead on fossil fuel emissions per stage of the supply chain? These are the emissions IPCC models tell us must reduce by >90% by eliminating coal, oil, and natural gas from the production, processing, and distribution of our supply chains.

Some final thoughts:

1. This corporate commitment path seems no more fruitful than the policy avenue for ag. Even though PepsiCo got and deserves some kudos for disclosing something, what they disclosed is in some ways less impressive than the status quo.

2. Regen ag is not generating GHG emissions reductions even on par with the scale of adoption even when companies are achieving some adoption. So, like the scenarios I ran this morning, benefits are really variable and highly dependent on historical management 1980-2000 and 2001-2021, and generally still resulted in net positive GHG emissions. The best case in the scenarios I ran was a 5.7% reduction. So, not seeing the 40% emissions reduction potential, especially when you're moving scope 1 and 2 to scope 3 with the co-man trend. Why are we investing $$ in ag as a "climate solution" from either public or private pots? Should we not focus efforts onto assets and operations companies own directly, and limit upstream efforts to their direct suppliers? Otherwise, much energy, effort and money gets wasted trying to get to an obscure point upstream and the entire set of supply chain actors that sits between the farm and manufacturers (storage, export/import, primary processing, secondary processing, etc.) associated with lots of fossil fuel emissions gets ignored.

What does this mean for us?

We help clients understand the food system, assess opportunities, and deploy resources in an effort to achieve a lot of different goals, from cost-savings to climate chaos mitigation.

If both the public policy and private sector outcomes here seem subpar (to say the least), what's the alternative? What could we be recommending to people we work with that would make sense to our clients as well as serve to make meaningful change?

First, the key is to acknowledge the reality of these situations. Without an honest and candid understanding of the facts, and how existing projects and opportunities are and are not working, we can’t possibly move forward.

Secondly, our work has shown again and again that the best solutions, the really, really impactful ones, are simply not that scalable in the cookie cutter sense. They aren’t easy to write into a $800 billion bill in a few paragraphs, nor are they simple to implement across a complex global supply chain. They are not splashy (i.e., affecting hundreds of thousands of acres) or easy to convert into reduced CO2e. They're projects and investments that empower communities and that shape the way that people think about landscapes. The genuinely most successful projects are those that completely rethink our ideas about feeding people and animals (from the farm to the corporation) at a smaller scale. It's thinking about resilience and adaptability instead of mitigation and prevention.

That’s the call to action here. Eventually, maybe in two years, or five, or ten, we’ll all laugh at much of the ineffective "work" that's going right now in the private and public spaces around regenerative agriculture. We'll be laughing because we will have evolved passed the first generation of climate-ag investment and into the second, third, and beyond, and we'll be conscious of how fruitless generic, broad-brush USDA programs are, and how ineffective it is to expect that every major food corporation will have a climate-ag portfolio much like any other, rich in "data" and splashy numbers but low in compelling qualitative evidence and community input and in that way, unable to break through the noise to capture hearts and minds, and thus create meaningful and lasting change.

As climate impacts become more and more severe, major multinationals (setting aside USDA) will become increasingly dependent not on moving their supply chains/sourcing around the globe more a frequently to less affected regions (which could quickly become cost prohibitive), but on closer relationships with key players in key producing regions. There's some power shifting happening there-- and the more climate impacts expand, the more powerful individual groups and regions become as compared to a global company who’s strategy is dependent on having access to many sellers and whose power is dependent on being able to move on when prices get "too high." When the amount of a crop is meaningfully limited in the world by adverse weather effects, that situation will be different, and I think those organizations that have invested in deep, collaborative relationships and investment within their regional supply chains will fair far better then those who aren’t. And government agencies that are aiming to support American food security and resiliency would be wise to invest in this relationship building sooner rather than later.