The Great Homestead Debate

would more Homesteads Make Our Food System Better?

At Grow Well, we (Alison, Sarah and Mariko) recently got into an extensive debate about whether homesteads have a role to play in a better food system of the future.

We’re a diverse set of individuals with a big range of backgrounds— from growing up on hobby farms in rural settings to growing up backyard gardening within the limits of one of the largest cities in America. We bring varied personal and professional perspectives to this very sticky subject, and we spent so much time talking to each other about it, that we wanted to share our thinking and hopefully, learn even more.

For us, all of this had to start somewhere, and we started disagreeing right at the beginning— about the very definition of a homestead. Alison tackles that in this first segment, with additional segments from all of us in the works.

Round 1: What is a Homestead, anyway?

I’ve thought a lot about the friction in this debate stemming from actual origin or definition of the word ‘homestead.’ So, I decided to look more into what that actually was.

Before actually looking anything up, I'll share that my perception was that the word was largely an American construction born of the Homestead Act of 1862. This perceived origin gave the word itself inherent charged tension; between the positive home half and the all the warm fuzzy promise wrapped up there, juxtaposed with stead, which had a much more negative charge to me. I attributed this to some vague mental imagery of individual European American nuclear family's steading or staking out their homes equating with simultaneous violent eviction of communities of Native American families from their homes.

Turns out I was wrong and a little bit right.

The word is way older than I thought. Merriam-Webster says its first recorded usage was before 1200, and variations of it are widely conserved across northwestern European languages. There are or were German, Dutch, Danish, and English versions of homestead.

Original versions of the word did not carry the individualistic nuclear family connotation of later American usage. Both Old English and German versions held the fixed residence portion of the meaning, but were more synonymous with "village" or hamlet (same root word) than just limited to an individual family. Their meaning centered more on the home and stability parts "to settle, dwell, be home;" possibly even more in a group of dwellings or structures, than the sort of lone Little House on the Prairie imagery that my brain held for the word.

However, in terms of more modern usage beyond the 1200s, my notions were more correct.

Since the 1690s, the word has largely been understood as "a lot of land adequate for the maintenance of a family."

But, as our cultural definition of family has grown narrower, so has the definition of homestead. When usage peaked, the definition and control of the homestead was really even narrower than family - a single man.

The word is really predominantly American and its usage and popularity really rose and fell with the US' Homestead Act of 1862 and Canadian Dominion Lands Act of 1872. Both US and Canadian homestead acts specifically defined the amount of land adequate to maintain a family as 160 acres, 40 of which needed to be "cleared and cultivated" within 5 years to keep it. Usage followed the physical rush for converting these public parcels to private, with peak appearance in print in 1886, with a pretty precipitous drop until 1960. Homesteads did "scale" during the more than 100 years the act was in effect. By 1934, more than 270 million acres, more than 10% of the US land area at the time, had been distributed in homesteads. The US ceased recognizing/issuing homestead claims in 1976 in all states except Alaska. Alaska continued recognizing homestead claims until 1986.

Usage has mostly plateaued since then and notably remains far higher now than 1800-1860.

It's not exactly that only Americans use the term, but it's more popular in the US, gauging by search frequency, than anywhere else in the world. Other places where it remains in use share America's history with western European colonialism: New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa. Notably, usage in South Africa differs. The term there is most commonly applied to a collection of dwellings inhabited by a group of extended family members encircled by a fence.

So what exactly are modern definitions of 'homestead'?

Merriam Webster provides definitions of homestead, both as a noun and verb.

Noun:

1a: the home and adjoining land occupied by a family

b: an ancestral home

c: house

2: a tract of land acquired from U.S. public lands by filing a record and living on and cultivating the tract

Verb:

transitive verb: to acquire or occupy as a homestead

intransitive verb: to acquire or settle on land under a homestead law

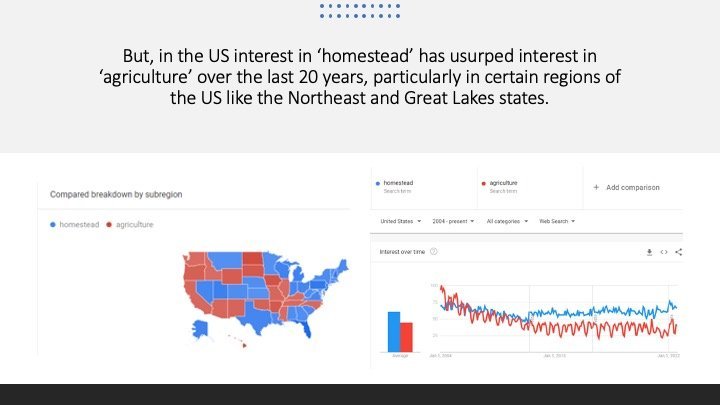

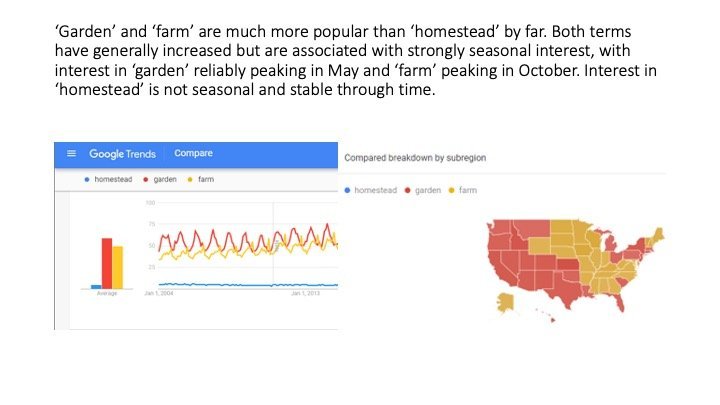

Homestead still apparently curries significant appeal or interest, more so than agriculture or farming. This may be because of the perceived accessibility of the smaller scale of engagement, as garden is even more popular than homestead.

However, unlike 'garden' which interest reliably peaks in around May, interest in homestead is much more static, suggesting maybe people are more interested in the lifestyle or home making portion of the term than with actually growing any crops or animals?

Farm is another story entirely. It's a way more popular search term than homestead as well, but it's even more strongly seasonal than garden - peaking hard in October when everyone needs their apple picking/pumpkin patching/ cider drinking fix?

Where does this leave us?

I guess my deep dive into where this word came from softened my attitude towards the word a bit and also made me revisit the true scale homesteading achieved. 270 million acres is more acres than we currently have in corn, soy and wheat combined. It's probably not a physical scale the term will achieve again, at least if limited to commercial agriculture.

The bit I found perhaps most interesting was the term's more communal original meaning. Not that I think communes are the way to go, but just that a collection of families living and working together in close proximity and in a way that they derive much of their sustenance from their interactions with the adjacent landscape is a concept that I see some merit/value in from both environmental and social perspectives.

That living/interacting part gets at that relationship with a place that I find to be so important and a big part of why I like gardening - the activity helps me notice plants, animals, weather happening where I live that make me better able to understand and steward the space to get more food to grow each year.

Personally, I also think about homesteading in the context of my own activities, including gardening at home, the community garden, and the mushroom business.

I have thought for a very long time about gardening for a more serious quantity of sustenance. Thinking about that ratio of calories and acres is something I get hung up on a lot. Can we produce the 730,000 calories per human per year we need in a different way that meets the average 10 humans supported per acre of “modern” industrial ag? I think there is a lot of untapped potential especially out in the suburbs. The 40 million acres of lawn we have is certainly not helping anything.

Especially in the last few years, I have grown a lot more potatoes, dry beans, and various corn. It still doesn’t replace the grocery store for us, but we had enough dry beans this year that I used the last container in chili in February and we’re still eating our way through the 2021 dresser of corn and walnuts in the basement.

But, maybe more importantly in the growing season March-December we have a surplus of lots of stuff to share with friends and neighbors. I have never kept good track of how much, but it does lead to a fun sort of bartering situation where I give someone a ton of lettuce and strawberries and they leave some honey from their hives on my porch. Or, I don’t have chickens but the folks I borrowed the grain mill from do and are happy to trade tomatoes and peppers for eggs. Their yard is too shady to grow any fruiting veg. Anyway, I have thought about if there is some way to scale up that type of system to be more meaningful which I guess was part of the genesis of the mushroom business. The idea that once you get good enough at growing something to produce it reliably for family scale, you inevitably have surplus, so maybe market it?

We have grown mushrooms since 2017, and it was a fun, relatively low-effort, low-cost hobby with delicious results. We scavenged oak from folks who needed something cut up or that came down in hurricanes. In 2020, the world went to sh!t and my spouse needed a different kind of meaning than he was getting from his job at the time. So, he decided to try to see what more we could do. He was in an MBA program at the time, so he planned the hell out of it and did more intensive accounting on it than your average analyst at a NY M&A firm. He came up with a production plan and we built grow rooms in our basement. We grew quite a lot of mushrooms, but it quickly became clear that the marketing half of the equation was not an insubstantial task and I began spending increasing amounts of time to move said mushrooms. We did get customers. We did several thousand dollars in sales last year, which considering we were running the whole thing in half our basement and in our suburban backyard didn’t feel too shabby. But it was a far cry from anything it would take to replace a job.

It also took every second of our lives. He was pasteurizing substrate at every hour of the day and night. The fans broke down and led to mold that caused me to have asthma attacks and us to have to cancel a week of orders. At the beginning I had said we needed to start selling them because I was tired of eating mushrooms at every meal. At the end, we rarely ate mushrooms ourselves because we were always scrambling to meet orders. It just wasn’t working. So, we’re on hiatus. I think we’re permanently done with indoor growing, but we may still sell surplus shiitake and wine caps and chicken of the woods when we have big outdoor flushes. But, you need relatively uniform consistent supply to run a business and outdoor growing isn’t that. Or, maybe we’ll eat what we can, dry the rest and mail them to relatives as holiday gifts.

In the end, I still don't self-label as a homesteader. In part because I chafe at all labels. Labels feel like an unnecessary bounding of possibility. And, in agriculture, as in the rest of life, it feels important to keep all options open. Especially options that may borrow the best from several production systems melded together into something we don’t yet have the word for.

This is far from the end of our debate! Stay tuned for more coming rounds of discussion on the benefits and drawbacks of homesteading, and feel free to chime in! We’d love to hear what you think about the debate.